Join the Leading Global Eye Health Alliance.

Membership-

Choose an alternate language here

The Sustainable Development Goals aim to leave no one behind, We are all working to reduce visual impairment, but do we know if some people are being left behind? write Jacqueline Ramke and Allen Foster.

If we do outreach, are we sure we are reaching all the people who need services? In this blog we discuss some challenges we must overcome to improve equity of eye care and leave no one behind.

This is the message of the inverse care law, which states that the availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served. The law was proposed by British GP and NHS advocate Julian Tudor Hart[1] in 1971. We see the inverse care law in eye care, with the areas of the world with the highest prevalence of blindness also having the fewest service providers[2]. We also see it within countries where the most socially disadvantaged—commonly poor, rural women—have the least access to eye care and highest rates of visual impairment[3].

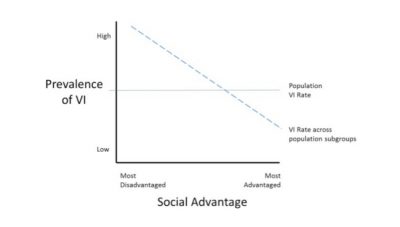

The inverse care law is one reason for health gradients that see health vary across populations with social advantage. An example is shown below, where prevalence of visual impairment is highest in the most disadvantaged and decreases as social position improves, to be lowest in the most socially advantaged.

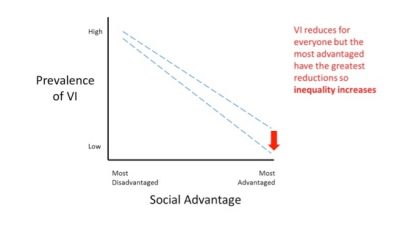

This is the message of the inverse equity hypothesis[4] and occurs because the more advantaged tend to take up new services at a faster rate than the socially disadvantaged. This is shown in the figure below.

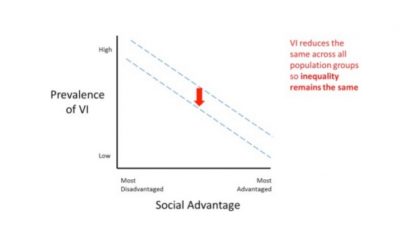

Where blindness is distributed unequally across population groups, delivering services equally to these groups will reduce the overall prevalence rate, but the level of inequality between the groups will remain the same. For example, if women have 60% of cataract visual impairment, women receiving 50% of cataract services will not reduce inequality between women and men.

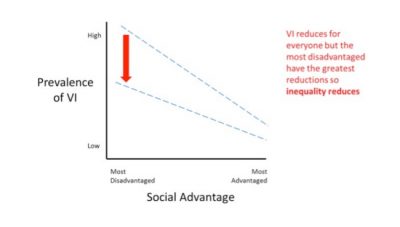

A way forward: When services are delivered proportionate to need, inequity is reduced

A way forward: When services are delivered proportionate to need, inequity is reducedTo reduce inequity, we must reduce vision impairment among the socially disadvantaged at a faster rate than among the more advantaged. This strategy—known as proportionate (or progressive) universalism[5]—aims to improve health for the whole population while targeting disadvantaged groups to ensure that improvement flows proportionate to the level of disadvantage, with the greatest benefit in the most disadvantaged, the next greatest benefit in the next most disadvantaged group and so on (shown below).

To reduce inequity in eye health—and leave no one behind—we must urgently strengthen two areas.

First, we must collect information on the social distribution of visual impairment and service use. Second, we must use this information to set targets, plan, implement and monitor strategies to deliver services proportionate to need.

At ICEH[7] we are beginning a project to address these needs, and would welcome the opportunity to learn about the equity-oriented projects of our IAPB partners.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jul/12/julian-tudor-hart-obituary

[2] https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/40067/1/TheGlobalInverseCareLaw.ADistortedMapofBlindness.pdf

[3] http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/3548962/

[4] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(00)02741-0/fulltext

[5] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)62058-2/fulltext

[6] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)61427-5/fulltext

Hosseinpoor AR, Bergen N, Koller T, et al. Equity-oriented monitoring in the context of universal health coverage. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001727. http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001727

Kelly MP. The axes of social differentiation and the evidence base on health equity. J R Soc Med 2010;103:266-72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2895530/pdf/266.pdf

Ramke J. Measuring inequality in eye care: the first step towards change. Community eye health 2016;29:6-7. https://www.cehjournal.org/article/measuring-inequality-in-eye-care-the-first-step-towards-change/

World Health Organization. Handbook on health inequality monitoring with a special focus on low-and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. http://www.who.int/gho/health_equity/handbook/en/

Photo credit: An old person with Cataract. Photo by Amitava Chandra; WSD #MakeVisionCount Photo competition.

Jacqueline Ramke is a Commonwealth Rutherford Fellow. Her position at ICEH is funded by the United Kingdom government through the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission in the UK. She has written this piece with Allen Foster, Lead, Disability and Eye Health group, ICEH, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.