Join the Leading Global Eye Health Alliance.

Membership-

Choose an alternate language here

The burden of eye diseases and visual impairment does not fall equally on the world’s population. Women and girls experience a disproportionate amount of sight loss, especially in low-and-middle income countries (LMICs).1 Women represent 55% of the world’s 43 million people who are blind2 and 55% of the 295 million people3 with moderate to severe visual impairment (MSVI). They even experience 35% higher odds than men of developing eye conditions that can lead to visual impairment and blindness.1 The most concerning aspect is that forecasts indicate that aging populations, changing lifestyles, and population expansion will cause a spike in the need for eye care globally in the upcoming years.4 Gender disparities in eye health are largely unaddressed and can impact an individual’s quality of life.5 The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these trends in recent years, and studies show that gender-disaggregated patient attendance to eye health clinics and cataract surgery rates have since widened between men and women.6

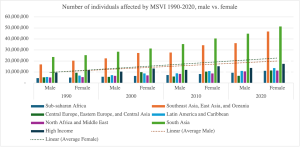

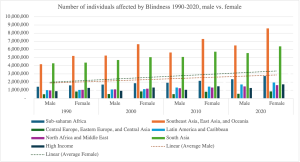

According to the IAPB Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Super Region Map7, the population numbers affected by vision loss is captured in decade increments by super regions for all ages and sorted by gender and type of vision impairment.2 This interactive database includes analysis and studies from the Vision Loss Expert Group (VLEG), a global technical international group of experts who specialize in ophthalmic epidemiology.8 In creating Figures 1 and 2 below, I observed that since 1990, more women are affected by MSVI and blindness than men on average across the super regions.

While this database shows the number of people affected by MSVI and blindness from 1990-2020, I can only descriptively analyze trends in gender disparities as it relates to eye health over time. Without publicly accessible quantifiable data, it would be difficult to parse out gender disparities from other eye health disparities in this database contributing to worsening eye conditions. According to Figures 1 and 2, it can be observed that gender disparities contributed to worsening patterns in MSVI and blindness for more women than men on average. These worsening patterns across the super regions can be explained by a few descriptive examples of gender inequalities. In sub-Saharan Africa, female family members must seek permission from the male head of the household to attend community meetings or health clinics.9,10 In Latin America and the Caribbean, intersecting forms of discrimination result in harmful stereotypes that make accessing eye care services difficult for women in these countries.6,10 For example, girls who already suffer from vision impairment are kept home from schools due to stigma.6,10 In Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Oceania, elderly women are often socially excluded once they have suffered from vision impairment or loss, leaving them housebound and unable to access eye care information or services.6,10 In South Asia, studies show that there is an elevated risk of rural women developing cataracts due to their primary roles as caretakers and being responsible for the cooking in the household.6,11 In North Africa and the Middle East, the unequal distribution of human resources for eye health (HReH) across the countries exacerbates access and utilization of eye care services for women in rural areas.6,10 In Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, young mothers who are diagnosed with low anemia suffer from an increased risk of corneal and retinal disorders.6,12 And lastly, in high income countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, etc., insurance coverage, income levels, and low eye health literacy contributes towards worsening patterns of women suffering from MSVI and blindness over time.13

Given that gender equity in eye health is a relatively new priority in the global health agenda, I hypothesize that by 2030 there will be improvement in MSVI and blindness trends for women and men on average. However, gaps in data collection prevent us from being able to parse out which exact disparities are contributing towards MSVI and blindness as the database currently stands.2,6 There is also no data disaggregated to capture MSVI or blindness prevalence for LGBTQ+ or other marginalized populations on a region or country level either. Data collection can be challenging for these groups as societal stigma, discrimination, and violence would make them reluctant to disclose their sexual orientation or identities.14 This gap in knowledge contributes to differences in eye health outcomes and needs further concerted efforts to improve data collection and research.

Although gender disparities may improve over time in eye care, vision loss is projected to increase by 55% over the next 30 years.7 Age-related eye conditions like cataracts and AMD may worsen global prevalences of MSVI and blindness.7 With population growth expected, lifestyle changes are imperative to decrease the risk of vision loss globally and close the gender gap.1

References